Accessibility Map

Providing navigational information to those who struggle with access

July - December 2021

Click anywhere to exit

Disability is a Spectrum

No two people who identify as disabled will share the same lived experience. Some people will only experience a disability temporarily, like a broken leg, or situationally, like trying to open a door with arms full of groceries. Even between two individuals with the same disability, the word "accessibility" might hold two different meanings: a barrier to one person might not be a barrier to another. While accessibility is a unique, personal experience for an individual, the lack of generally available accessibility information for buildings—for instance, those that are part of a school campus—makes any trip to a new location an ordeal for some people who have a disability.

Many college campuses have little to no information about building accessibility for students and community members. Part of this is that many schools often devalue disability support and treat accessibility as an afterthought, opting to address issues through accommodations as they come up. This accessibility map is a proactive step to helping schools provide a beneficial resource to their students to get around campus with greater ease and less worry about accessibility barriers they might encounter. I completed this project on my own over approximately six months.

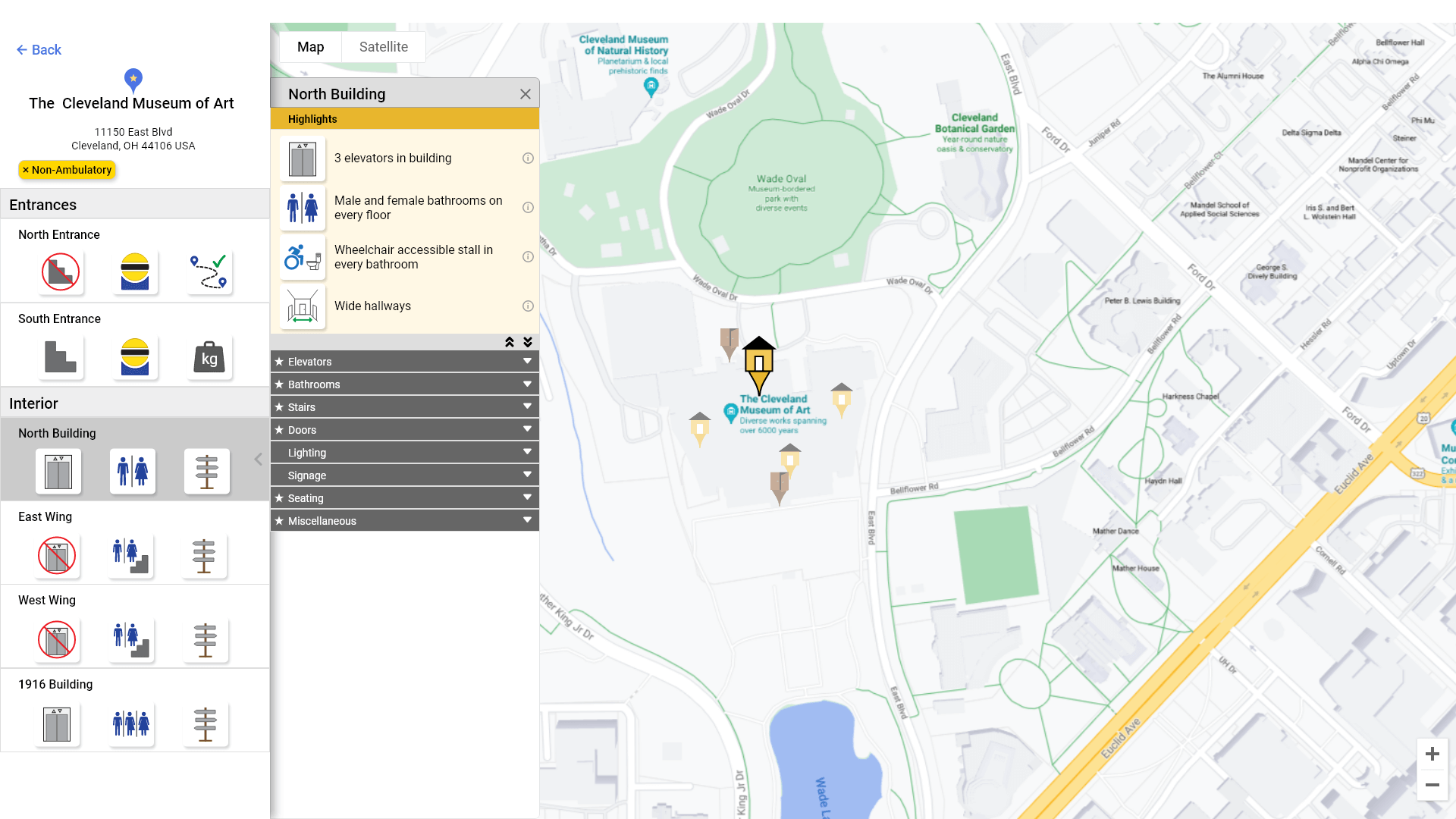

This is the Accessibility Map!

Purpose

This project aimed to create a resource that provides campus community members and visitors with foreknowledge of potential barriers in their environment in the form of a map. The map will call out specific accessibility information for each building on campus, highlighting areas where barriers might exist. This project intends to allow individuals with disabilities to better plan their outings with confidence and a feeling of inclusion.

Requirements

To create a unique, useful, and impactful tool, I focused on achieving the following:

- Highlight information that typically factors into accessibility issues.

- Benefit a wide audience.

- Make the map itself accessible and easy to use.

Discover

Accessibility Research for Built Environments

A clear starting point for this project was first to understand better what accessibility meant in a built environment. To do this, I spent a day exploring a variety of sources—from books to blogs, to articles, to videos— that shared insight into life with a disability. You don't have to dig far before you find a wealth of information.

Some critical insights gained from this research are the following:

- There's so much more to accessibility than simply whether or not a building entrance has steps.

- Accessibility must be comprehensive to be most beneficial: a level entrance is only so good if the door is too heavy to open without assistance.

- Inaccessibility can cause mundane errands to be major ordeals for someone with a disability.

- The fear of unknown accessibility often deters individuals with disabilities from going to new places.

Forethought at its finest

Accessibility Standards

We live in a world built for people without disabilities, but thankfully there are standards to ensure accessibility for those who need them. Title II & III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) outline accessibility standards for facilities to prevent all state and local government entities and all private entities from discriminating against people with disabilities.

Unfortunately, theory always differs from practice, and the ADA standards are not all-encompassing, partially due to the inability to perfectly capture the accessibility needs of everyone but also due to the practical need to offer exemptions for special cases. Specifically, Title III forgoes requiring private entities to remove architectural barriers where such removal is not "readily achievable." Title II forgoes requiring compliance for existing facilities in cases where an "undue burden" would be involved for the public entity. These open-ended standards leave room for interpretation when determining a facility's compliance and fail to answer the question, "What barriers might still be present in an ADA-compliant building?" So while helpful, more than the ADA is needed. We need something more.

Define

Who are we designing for?

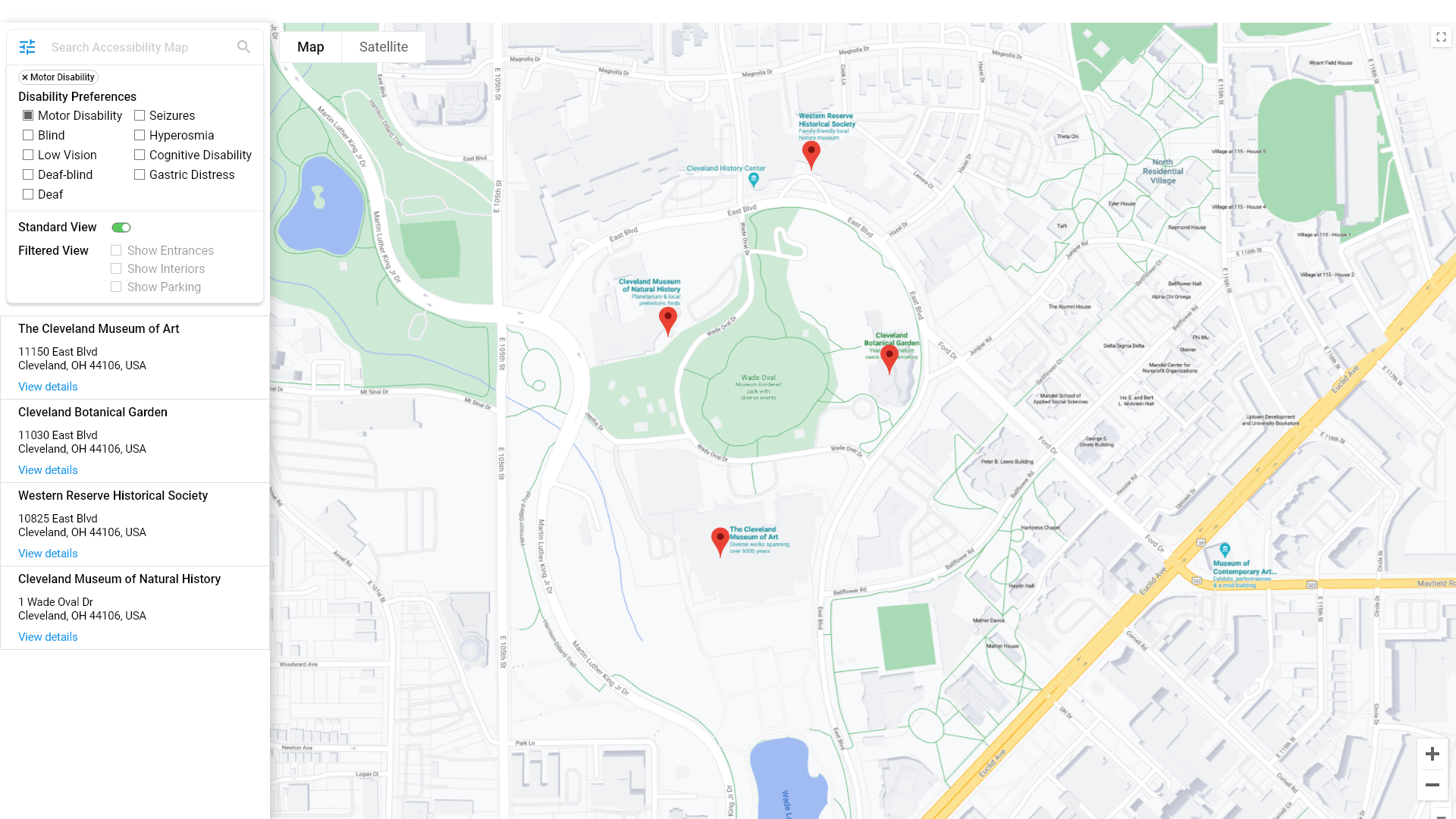

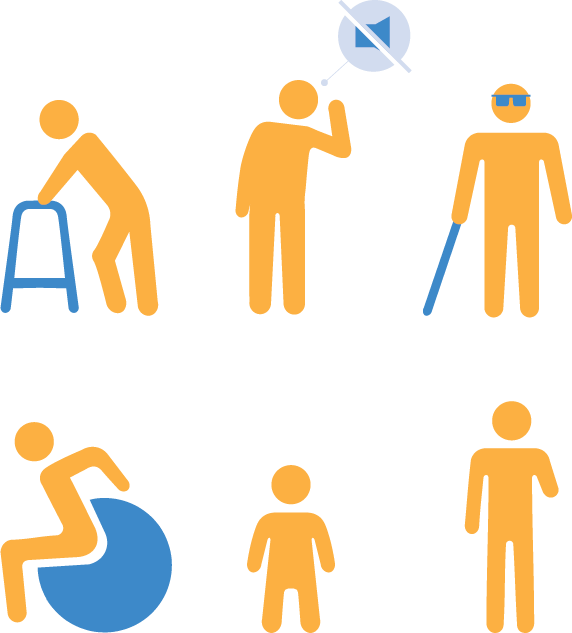

As I've mentioned, disability is not a one-size-fits-all, so it's not enough to design this project for "people with disabilities." What types of disabilities are we designing for specifically?

To name a few, we are designing for those who experience:

- Blindness

- Low Vision

- Color-blindness

- Hearing Impairment

- Paraplegia

- Dwarfism

- Limited Dexterity

- Cognitive Disability

- Reading Disability

- Seizures

Just a few populations impacted most by accessibility barriers

Problem Statement

People experiencing a disability—permanent, temporary, or situational—need better support to overcome barriers in their environment and confidently navigate their world without feeling excluded. Many spaces are not designed with people with disabilities in mind, leading to accessibility issues that require afterthought-accommodations and infrastructural add-ons.

When put in the context of students navigating a school campus, inaccessible spaces can lead to barriers to entry for those seeking higher education. This fact is further emphasized by the following statistics for the US population:

13%

Of US citizens have a disability

32%

Have some college education

15%

Have an undergraduate degree or higher

Establishing Accessibility Criteria

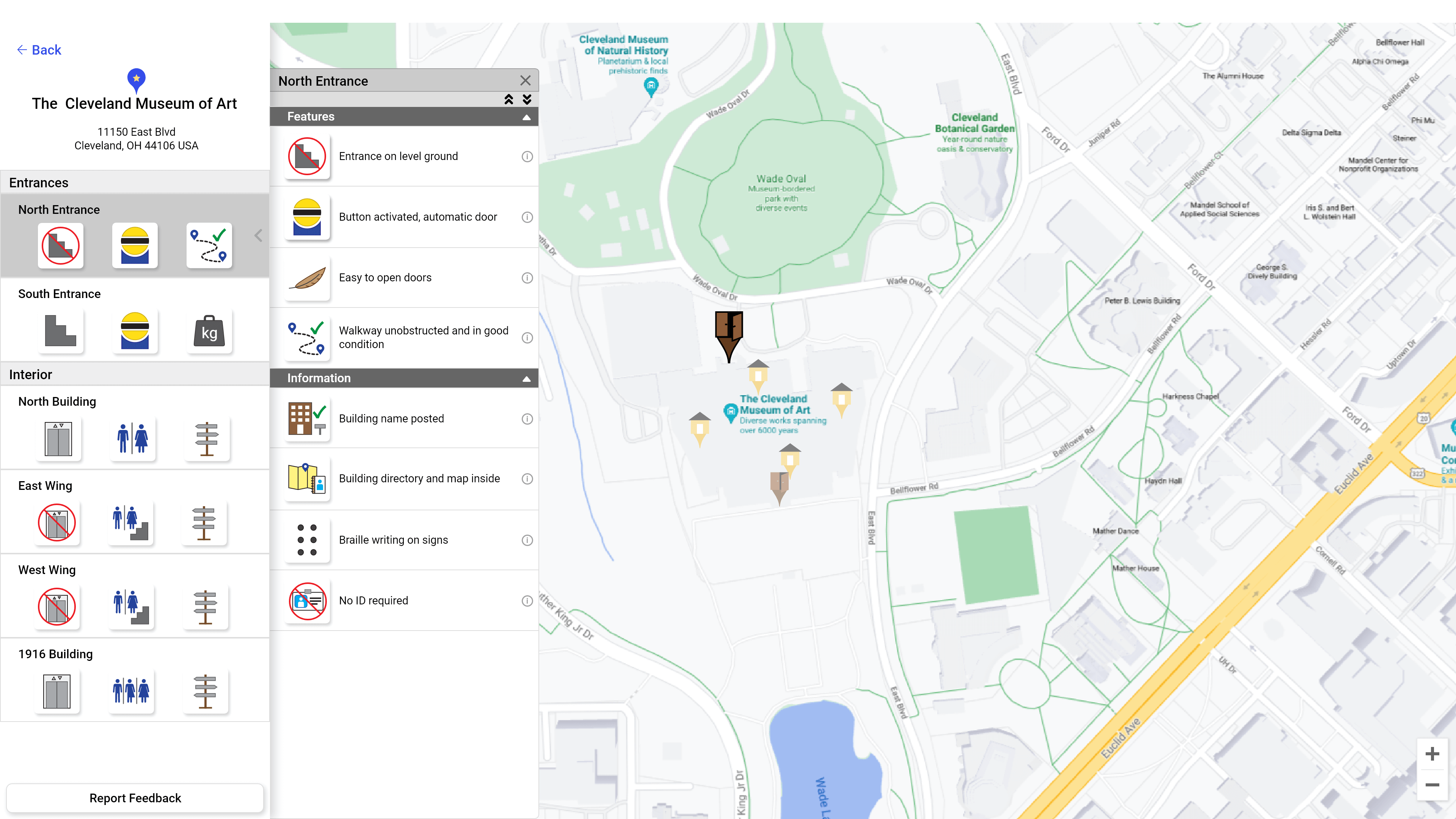

Before jumping into design, it was necessary first to define a list of criteria that could be used to evaluate each building. I needed to determine what information was most important for this map to capture to benefit the most significant number of people. Knowing what data the map would display, I could use this information to determine the visual layout of the design.

I used knowledge and examples from my earlier accessibility research to determine any easily identifiable criteria. Additionally, I conducted an empathy exercise where I first created a list of common university navigation patterns—such as walking through connected buildings, up and down building levels to get from one classroom the another. I then mentally moved through these patterns while focusing on a specific disability and commonly associated access needs to identify potential barriers individuals with this particular disability would encounter. Research and this exercise allowed me to generate an initial list of criteria for which I then sought validation from individuals with various disabilities through surveying.

Develop

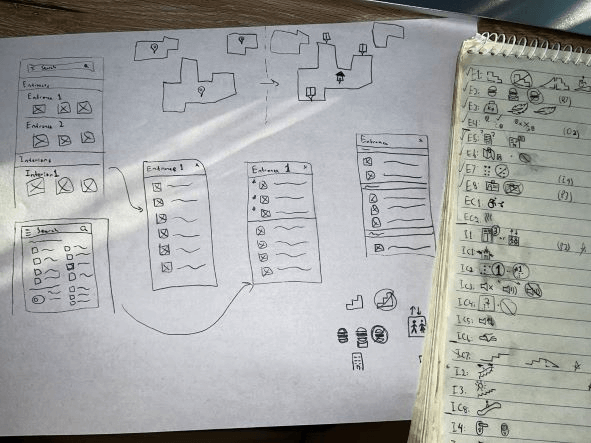

Messy but they get the job done

Ideate

Diving into creating the design, I first produced a list of ideas based on user feedback, usability considerations, and accessible design practices. Then I began to bring my ideas to life through sketches, playing around with the exact layout and how I would display information.

While moving into this phase of the design process, I had three significant focuses that drew from the principles of universal design:

- Make the design flexible by providing a customizable experience.

- Make the information perceptible by offering multiple means of representation (i.e., visuals, plain English text, and screen reader-friendly alt-text).

- Make the design simple and intuitive by streamlining navigation and how information is displayed.

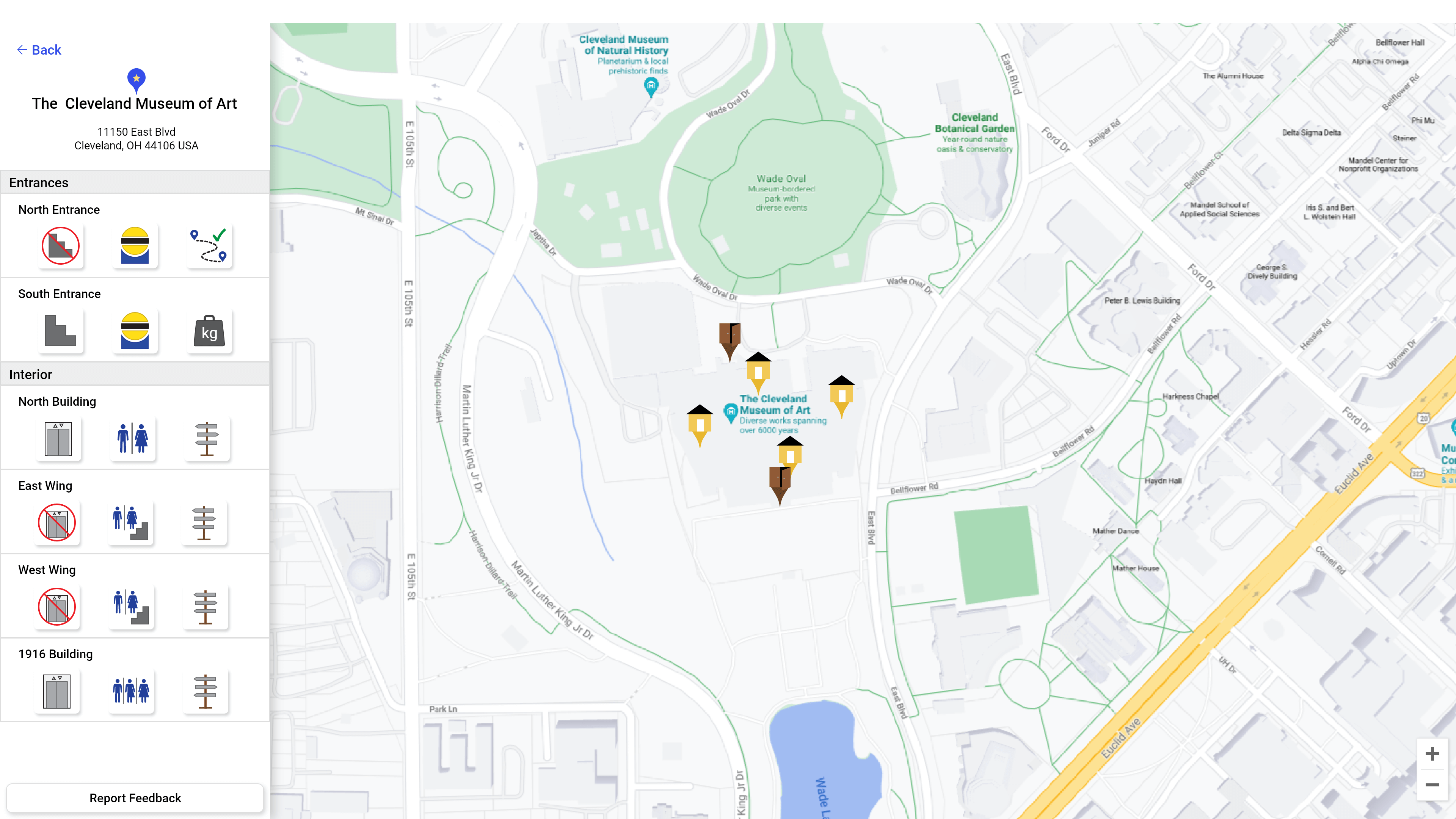

Visual Icons

Concise and simple English is the primary means of communicating information in this design. However, to supplement information, reduce cognitive load, and curate a more aesthetic user experience, I created a library of icon sets for each criterion to represent the various possible states visually. I designed these icons to help facilitate quicker consumption of information and make the overall product more usable.

Offloading cognitive load by providing visual communication

Retrospective Note

In hindsight, I was trying to communicate too much through these icons. A part of me knew that, but it felt like a necessary consolation to present all the information. Thankfully, in Accessibility Map 2.0, we don't have the same issue, and the information is presented in a more consumable manner.

--November 2022

Deliver

Prototype

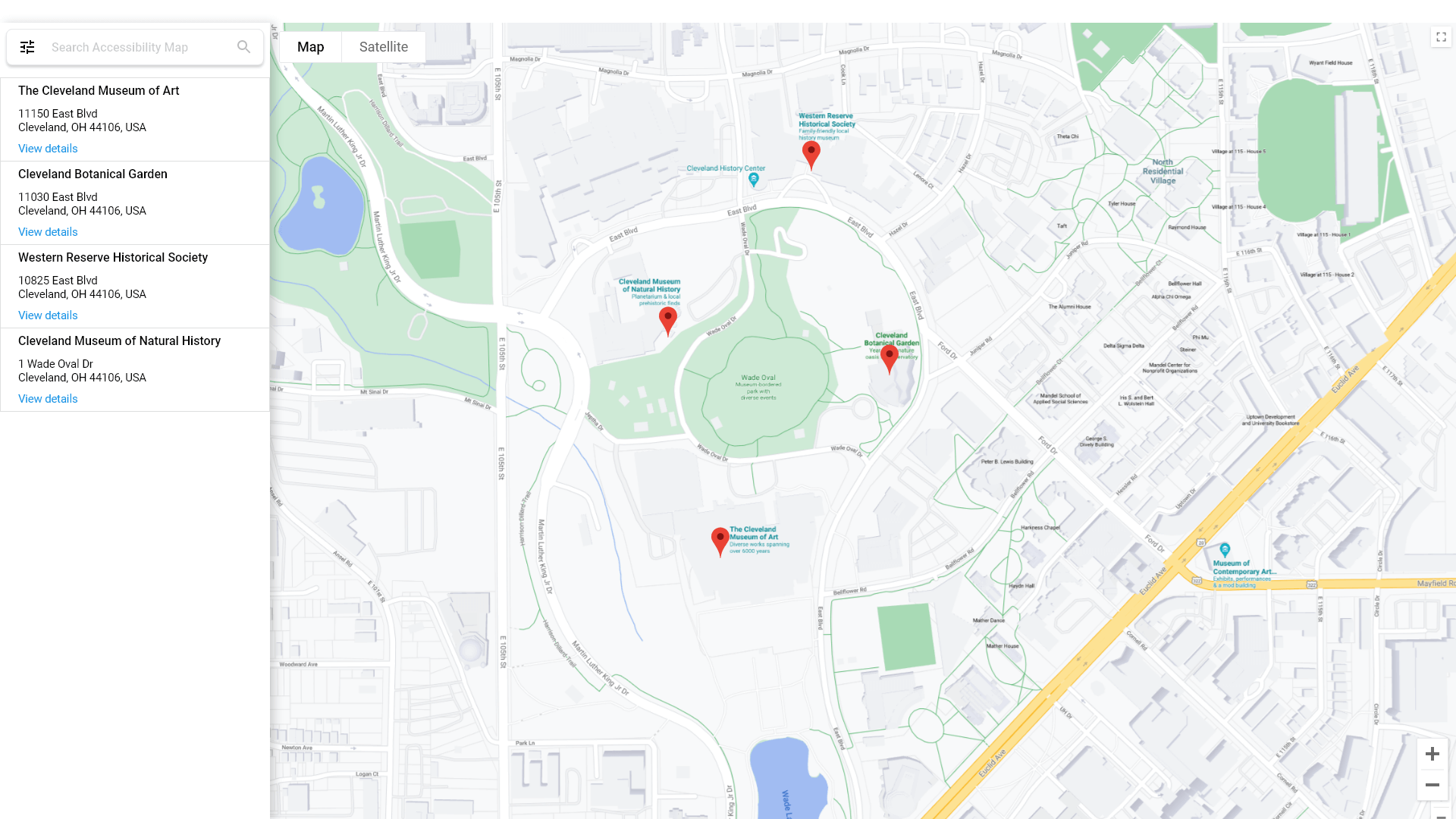

Bringing my sketches to life, I created a clickable prototype. The final product will utilize Google Maps API, so styling for the map borrowed inspiration from Google's styling, with some intentional alterations.

Usability Testing and Accessibility Auditing

To validate the design, I first conducted a usability test with five users, testing their ability to navigate through the design, find specific pieces of information, and use the filtering options to change the view of information. Overall, users successfully and effectively used the design without significant errors/issues.

Next, I conducted an accessibility assessment to review the design's accessibility, such as word choice, color contrast, and visual sizing. I outlined accessibility elements that will come later in development, such as alt text, tab index, and semantic ordering. I will conduct more in-depth accessibility (as well as usability) testing once I complete product development.

Conclusion

Development is still currently underway for the final product. Once I've completed further testing, this map will be implemented at schools, such as Cleveland State University and Case Western Reserve University, and provide their campus communities with a valuable tool to identify barriers to accessibility in their environment. This tool will be not only of use to community members with permanent disabilities but also to those who are experiencing a new or temporary disability.

Retrospective Note

Since the initial creation of this showcase, this project was completed at Cleveland State University. To view the map visit http://csu.constellarmap.com

--May 2022

Home

Home